|

Click any typewriter

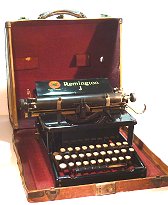

Remington 7 - 1895

Understrike typewriter

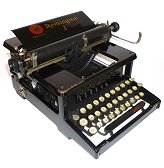

Remington 10 - 1910

Visible typewriter

Remington

Junior -1914

'Luggable' typewriter

Remington

Portable 1920

Remington

Portable #2 1925

Remington

Portable #2 1927

Remington 3 Portable 1933

|

Remington had been the

leading maker of desk typewriters since the company

produced the first successful machine in 1878, after buying the patents of

Christopher Sholes and his co-inventors. This commercial dominance

was due primarily to William Wyckoff, Clarence Seamans and Henry Benedict -

names that adorned desks all over the world on Remington 7 and Remington 10

desk machines (see left). But by the time

the First War ended in 1918, the industry

had changed radically - typewriters had become portable. Remington had been the

leading maker of desk typewriters since the company

produced the first successful machine in 1878, after buying the patents of

Christopher Sholes and his co-inventors. This commercial dominance

was due primarily to William Wyckoff, Clarence Seamans and Henry Benedict -

names that adorned desks all over the world on Remington 7 and Remington 10

desk machines (see left). But by the time

the First War ended in 1918, the industry

had changed radically - typewriters had become portable.

Remington's first attempt to adapt to changing

markets was the Remington Junior of

1914 - the result of a joint effort between Remington and Smith Premier

(the two companies had merged in 1893).

It was manufactured in the old Smith Premier factory in Syracuse and

the design seems to have resulted from a collaboration between Arthur Smith

and John Barr of Remington, and Emmit Latta of Smith Premier. It differs

from the Remington 10 desk machine

in several important respects. Most

obviously, it has a three-row keyboard with two shift keys to provide the

full range of characters. The Junior’s mainframe is fabricated from

pressed steel, rather than cast iron. This results in a significant weight

saving, but the machine still weighs 16 pounds (against the Corona 3’s 7

pounds) making the Junior ‘luggable’ rather than truly portable. The

machine also employs the idiosyncratic ribbon mechanism designed by

Emmit Latta for Smith Premier in 1904.

In this arrangement, the ribbon spools are mounted at the rear of the

machine and fed under the carriage. It was so fiddly, that Remington

provided a special tool with each Junior for snagging the ribbon end and

drawing it through. It’s

thought that machines made for export to Europe bore the letter J on the

paper table, rather than the name ‘Junior’, like the machine illustrated

here.

The Junior was manufactured until 1919 when Remington finally caught up with

its main rival, Underwood, and responded to market demand for truly portable machines.

In October 1920 the company unveiled the Remington Portable shown below left. The

Remington Portable of 1920 was designed primarily by John H Barr, a

professor of machine design and mechanical engineering at Cornell

University. Barr was granted the patent for the Remington four-bank portable

on October 28, 1919. Almost exactly one year later the machine went into

production at Ilion in New York. According to the first edition (August 2,

1926) of The Remport - a newsletter for Remington portable sellers,

"The Remington Portable was first exhibited at the New York Business

Show in October, 1920. Its manufacture began shortly thereafter but for many

months only a limited number of machines were available for

delivery." The wait proved to be well worth while. Barr

and his team had created a sleek, low-profile machine with a full four-row

keyboard, just like its best-selling Remington 10 desk machine, but with the

works slimmed down dramatically. To appreciate fully the extent of the design team's

achievement, compare the Remington Portable with the company's standard desk

machine of the time, the Standard 10 (shown below). The keyboard is the

same size and layout as that of the desk machine, but everything else has been

miniaturised and crammed into a sleek box only an amazing three inches high.

This streamlined, low-profile design was an augury of the times, heralding the

Art Deco movement that was to  revolutionise industrial and interior design in

the 1920s and 1930s -- indeed the Remington Portable design is so far ahead of

its time, it is reminiscent of machines of the 1950s. The side view

shows how successful the

Remington engineers had been at meeting their design brief for the slimmest most

modern looking portable possible with current technology. The Remington

Portable of 1920 was not only beautifully

designed, it was also very easy to use because the shift mechanism moved the

carriage - not upwards - but smoothly backwards, almost horizontally, with

scarcely any effort. Remington quality was evident throughout in the

engineering and the marketplace greeted the new machine in much the same way

that IBM customers reacted to the introduction of the Personal Computer in 1982.

They bought the Remington Portable in tens of thousands.

The Remington factory in Ilion, New York, shown here, extended its

production capacity still further and the picture postcards boasted it was

able to manufacture a typewriter every minute.

Perhaps the one design flaw with the early Remington

Portables was that the engineers failed to deal satisfactorily with the need to

lay the type basket flat when the machine was stowed away in its case, and so

resorted to the clumsy device of having a typebar raising lever (see left) that had to be

pushed home to raise the typebars to the ready position before typing could

begin. This clumsy device was eliminated from the Remington Portable model

3 onwards, introduced in 1928 (see below left) and competing with the Remington

Noiseless as one of the most beautiful portable typewriters ever produced. As

early as 1876, Remington had a factory in London. What was manufactured in

London is not known with any certainty as every Remington desk typewriter

carried a clear message that it was "Manufactured by Wyckoff, Seamans

and Benedict, Ilion New York ." It may be that US-made export machines

for the British market were adjusted here. However, after the introduction

of the Remington Portable, the company began shipping manufactured parts

across the Atlantic for assembly at its London factory. These British

machines carry a notice informing customers that they were "Assembled

by British labour at the London factory of The Remington Typewriter Company

Ltd." Usually they did not carry the familiar red Remington seal

announcing that to "save time is to lengthen life" although the

example illustrated here does have it.The huge market success of this machine prompted Remington to embark

on a design spree for portables that lasted for fifty or more years. revolutionise industrial and interior design in

the 1920s and 1930s -- indeed the Remington Portable design is so far ahead of

its time, it is reminiscent of machines of the 1950s. The side view

shows how successful the

Remington engineers had been at meeting their design brief for the slimmest most

modern looking portable possible with current technology. The Remington

Portable of 1920 was not only beautifully

designed, it was also very easy to use because the shift mechanism moved the

carriage - not upwards - but smoothly backwards, almost horizontally, with

scarcely any effort. Remington quality was evident throughout in the

engineering and the marketplace greeted the new machine in much the same way

that IBM customers reacted to the introduction of the Personal Computer in 1982.

They bought the Remington Portable in tens of thousands.

The Remington factory in Ilion, New York, shown here, extended its

production capacity still further and the picture postcards boasted it was

able to manufacture a typewriter every minute.

Perhaps the one design flaw with the early Remington

Portables was that the engineers failed to deal satisfactorily with the need to

lay the type basket flat when the machine was stowed away in its case, and so

resorted to the clumsy device of having a typebar raising lever (see left) that had to be

pushed home to raise the typebars to the ready position before typing could

begin. This clumsy device was eliminated from the Remington Portable model

3 onwards, introduced in 1928 (see below left) and competing with the Remington

Noiseless as one of the most beautiful portable typewriters ever produced. As

early as 1876, Remington had a factory in London. What was manufactured in

London is not known with any certainty as every Remington desk typewriter

carried a clear message that it was "Manufactured by Wyckoff, Seamans

and Benedict, Ilion New York ." It may be that US-made export machines

for the British market were adjusted here. However, after the introduction

of the Remington Portable, the company began shipping manufactured parts

across the Atlantic for assembly at its London factory. These British

machines carry a notice informing customers that they were "Assembled

by British labour at the London factory of The Remington Typewriter Company

Ltd." Usually they did not carry the familiar red Remington seal

announcing that to "save time is to lengthen life" although the

example illustrated here does have it.The huge market success of this machine prompted Remington to embark

on a design spree for portables that lasted for fifty or more years.  The

company produced a bewildering array of designs, variations, colours and

specifications. It also pressed into service well-known typewriter brand names that it had

acquired, such as Monarch and Smith Premier. Remington's most successful

acquisition was the Noiseless Typewriter Company, whose silent typing technology

they incorporated into a successful range of both desk and portable machines

(including the machine shown as the Home icon on this site.) In 1927, Remington Typewriter Company merged with another office equipment

company, Rand Kardex, to form Remington Rand. In 1949, Remington Rand introduced

the first business computer, the Remington Rand 409. Instead of an auspicious

new beginning, however, the computer signalled the end of the Remington name. In

1955, there was another merger, with Sperry Corporation. This time the Remington

name was dropped and the new company was known simply as Sperry Rand. Although

no longer on the letter heading, the Remington name continued to appear in the

1950s and 1960s on a range of portable typewriters and electric desk machines,

before finally disappearing with the advent of the computer age it had helped

found. The

company produced a bewildering array of designs, variations, colours and

specifications. It also pressed into service well-known typewriter brand names that it had

acquired, such as Monarch and Smith Premier. Remington's most successful

acquisition was the Noiseless Typewriter Company, whose silent typing technology

they incorporated into a successful range of both desk and portable machines

(including the machine shown as the Home icon on this site.) In 1927, Remington Typewriter Company merged with another office equipment

company, Rand Kardex, to form Remington Rand. In 1949, Remington Rand introduced

the first business computer, the Remington Rand 409. Instead of an auspicious

new beginning, however, the computer signalled the end of the Remington name. In

1955, there was another merger, with Sperry Corporation. This time the Remington

name was dropped and the new company was known simply as Sperry Rand. Although

no longer on the letter heading, the Remington name continued to appear in the

1950s and 1960s on a range of portable typewriters and electric desk machines,

before finally disappearing with the advent of the computer age it had helped

found.

___________________________

One aspect of the Remington Portable that is of

interest to collectors is that its design underwent a very large number of minor

changes over the first few years of production, especially the first year.

Remington records describe the later, modified version as the Portable #2,

leading collectors to refer to the original October 1920 model as the

Portable #1. In reality, there is a

whole spectrum of changes between #1 and #2 and both versions are sought after by

collectors, but the very earliest one is naturally the most desirable. Below is a

list of differences to look out for.

Remington Portable #1

Points distinguishing early model

* The most obvious feature is that early machines, such as the one

illustrated above, have only one Shift key, on the left. According to Richard

Polt, Remington serial number records show the right hand Shift key as being

introduced in March, 1922 (#NL20211).

* The aperture cut in the top plate to accommodate the typebars terminates in

rectangular openings rather than curved ones.

* There are no curved guards protecting the ends of the pop-up type basket.

* Serial numbers are punched in the carriage bed rather than rear metal cover

frame

* Corners of cover frame underneath have raised blisters for feet, rather

than rubber grommets. Front frame has two holes for ‘push-through’ metal

retaining pegs in case bottom.

* There is no carriage return lever on early models and the paper is advanced

with a simple pinch-lever. Later machines have a vertical lever that both

returns the carriage and advances the paper (strikingly similar to the Columbia

Bar-Lock typewriter.)

* The platform on which typebars rest has no felt to cushion typebars when in

the ‘down’ position. This platform is a simple flat plate, with the works

visible under it. In later models, the plate has a circular protective edge.

* Space bar is made of wood, not plastic

* The paper table is curved in the direction of paper travel while later ones

are flat with rounded corners.

* The paper table on later machines has fold-away paper supports while early

ones have none.

* The line gauge or alignment scale -- the black triangle of metal that shows

the current line of typing -- is positioned centrally over the printing point on

early machines, but in later machines is positioned to the right of centre.

* Richard Polt observes that on early machines, the shape of the aligning

scale can vary: the opening can be either a plain triangle, or a sort of

upside-down, fat T.

* The type guide on early machines is a simple rectangle with a single

rectangular hole, while later models had an A-shape with two holes.

* On early machines the platen knob is only around ¼-inch thick; on later

machines it is twice this thickness and slightly barrel-shaped.

* The external cover panel is held in place by two screws at the top and two

at the bottom of each side. In later models two more screws were added at the

top. Later still oval cut-outs appears through which it is possible to access

pairs of screws on the internal frame.

* There is no automatic ribbon reversing mechanism on early machines. This is

visible in several ways. First there are no helical slots in the knurled knobs

at the ends of the ribbon reversing rod. Second, the knobs themselves are

relatively narrow and coin-shaped, rather than cylindrical. Third, there is no

pawl visible on the ribbon reversing ratchet beside the ribbon vibrator.

* The Line gauge (behind the ribbon carrier) is fixed by screws through two

holes, rather than two slots. (This makes it almost impossible to replace if

removed!)

* On early models, shift lock is separate from the shift key, so the typist

must first shift, and then lock. On later models the Shift key and Shift lock

key are linked so that the shifted platen can be locked with a single keystroke.

* The ribbon spools on early machines are held on by a small latch , in the

form of a cam, on the top of each spindle. On later machines, the latch is

absent and the ribbon spool slides straight over the spindle.

* Early machines do not have a right-hand carriage release lever.

* The line spacing lever on early models is fabricated from thin metal sheet

instead of a knurled knob.

* On early models, the paper release lever is pulled forward to release the

paper. On later models, it is pushed backward.

* There seem to be at least three distinct case designs, two of which are

illustrated here. The earliest case is 1-1/2 inches narrower than later cases

and its leather handle is fixed by slits over two round metal buttons rather

than under fixed rectangular retainers. The typewriter is fixed in place by side

and rear leaf springs in base of case. Two metal retaining pegs in base of case

hold front frame of typewriter.

* A later version has four metal studs in the case base which pass through

grommets in the typewriter frame and is attached by cotter pins to the studs. In

this version there is a lip that runs round the edge of the case.

* In the final version, the case base is flat and the machine is simply

screwed to it.

|